The Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ): What Your Score Actually Means—And What It Might Miss

By Lisa Long, Psy.D. | Licensed Forensic & Clinical Psychologist

You took the MDQ online, scored positive, and now you're wondering: Do I actually have bipolar disorder? Or maybe you've been treated for depression for years without much improvement, and someone suggested bipolar might be the real issue. Either way, you're looking for clarity—not another inconclusive screening result.

Here's the uncomfortable truth: the MDQ is a useful starting point, but it's far from definitive. Research shows that a positive MDQ result is just as likely to indicate borderline personality disorder as bipolar disorder in outpatient psychiatric settings (Zimmerman et al., 2019). That's not a flaw in you—it's a limitation of the tool itself. And understanding that limitation is the first step toward getting an accurate diagnosis.

What the MDQ Actually Measures

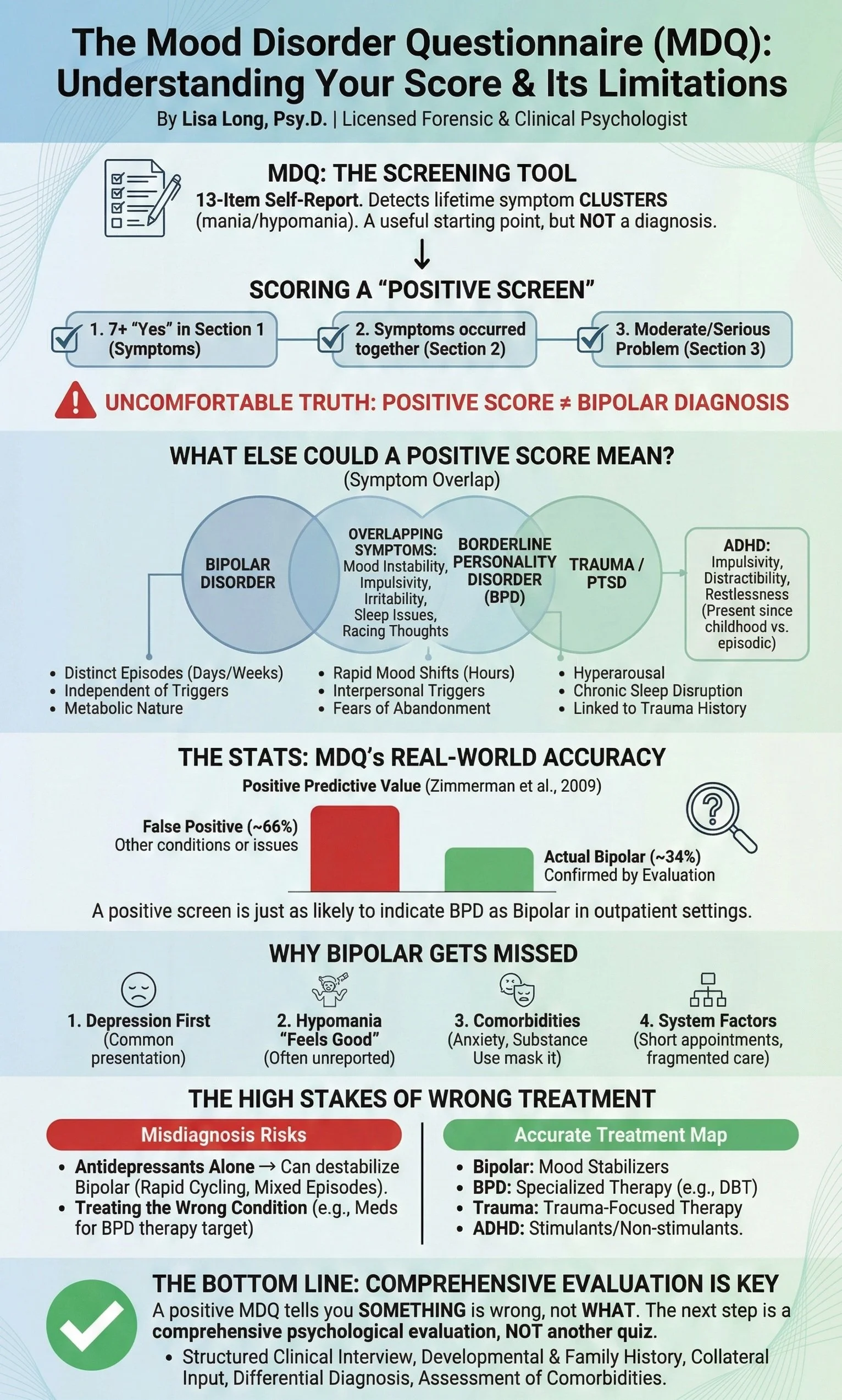

The Mood Disorder Questionnaire is a 13-item self-report screening tool designed to detect symptoms associated with bipolar spectrum disorders. It asks about lifetime experiences of manic or hypomanic symptoms: elevated mood, decreased need for sleep, racing thoughts, increased goal-directed activity, impulsive behavior, and similar patterns.

The core question the MDQ asks: Have you ever experienced a cluster of these symptoms occurring together, causing at least moderate problems in your life?

In the original validation study, researchers compared MDQ results to formal clinical diagnoses and reported 73% sensitivity and 90% specificity (Hirschfeld et al., 2000). However, subsequent research in broader psychiatric outpatient samples found the MDQ performed worse in practice—with sensitivity dropping to around 64% and the positive predictive value landing at just 34% (Zimmerman et al., 2009).

MDQ Scoring Guide

A "Positive Screen" on the MDQ requires meeting all three of the following criteria:

Seven or more "Yes" answers in Section 1 (the 13 symptom questions)

"Yes" to Question 2 — confirming that several of these symptoms occurred during the same time period

"Moderate" or "Serious" problem reported in Question 3 — indicating functional impairment

If you meet all three criteria, you've screened positive for possible bipolar spectrum disorder.

But here's what that positive screen actually means: In a large study of psychiatric outpatients, the MDQ's positive predictive value was only 34% (Zimmerman et al., 2009). In plain terms, roughly one-third of people who screen positive on the MDQ actually have bipolar disorder when evaluated with a comprehensive diagnostic interview.

Why so many false positives? The MDQ's symptom list overlaps substantially with other psychiatric conditions. The experiences it asks about—impulsivity, irritability, decreased sleep, racing thoughts, increased energy—also appear in borderline personality disorder, ADHD, anxiety disorders, trauma-related conditions, and substance use disorders.

A positive score doesn't mean you have bipolar disorder. It means you need a comprehensive evaluation to find out what's actually driving your symptoms.

Is It Bipolar, BPD, or Trauma?

If you scored positive on the MDQ but don't feel you fit the "classic" bipolar profile, you're not alone. The MDQ cannot reliably distinguish bipolar disorder from several conditions with overlapping symptoms.

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD)

In outpatient psychiatric settings, MDQ-positive patients are equally likely to have BPD as bipolar disorder (Zimmerman et al., 2010). Both conditions involve mood instability, impulsivity, and relationship difficulties—but the underlying patterns are fundamentally different:

Bipolar mood episodes are metabolic in nature, lasting days to weeks, often occurring independent of external triggers

BPD mood shifts are typically rapid (hours, not days), triggered by interpersonal stress, and tied to fears of abandonment or rejection

The MDQ asks about symptoms but cannot assess timing, triggers, or interpersonal patterns—the very features that distinguish these conditions.

Trauma and PTSD

Complex trauma and PTSD can produce mood instability that closely mimics bipolar presentations. Hyperarousal, irritability, sleep disruption, and "racing thoughts" are core trauma symptoms that the MDQ cannot distinguish from mania. If you have a significant trauma history, a positive MDQ may be picking up trauma responses rather than bipolar cycling.

ADHD

Impulsivity, distractibility, restlessness, and poor follow-through appear in both ADHD and bipolar disorder. The MDQ doesn't assess whether these patterns have been present since childhood (suggesting ADHD) or emerged episodically in adulthood (suggesting bipolar).

Emerging Research: Mood and Rhythm Dysregulation

Recent community-based research has found that many people who screen positive on the MDQ—even those without any formal psychiatric diagnosis—show patterns of mood instability, disrupted sleep, and reduced quality of life (Cantone et al., 2025). This suggests the MDQ may be detecting a broader pattern of emotional and biological rhythm dysregulation, not exclusively bipolar disorder. While this doesn't change the need for comprehensive evaluation, it confirms that a positive screen is clinically meaningful—even if the ultimate diagnosis isn't what you expected.

The clinical reality: Many people have more than one of these conditions simultaneously. Bipolar disorder commonly co-occurs with ADHD, anxiety, trauma histories, and personality pathology. Accurate diagnosis requires teasing apart which symptoms belong to which condition—something no self-report screener can do.

Why Bipolar Disorder Gets Missed in the First Place

The MDQ exists because bipolar disorder is notoriously underdiagnosed. The average time from first symptoms to correct diagnosis is approximately 10 years, and 50–75% of people with bipolar disorder are initially diagnosed with unipolar major depression (Yang et al., 2023).

This happens for several interconnected reasons:

Depression comes first. Most people with bipolar disorder present for treatment during depressive episodes, not during mania or hypomania. The depression looks identical to unipolar major depression—same symptoms, same severity, same suffering. Without careful probing for past elevated mood episodes, the bipolar pattern stays hidden (Yang et al., 2023).

Hypomania doesn't feel like a problem. Bipolar II hypomania is often brief and experienced as "finally feeling good" or "being productive for once." Patients don't report it because it doesn't feel like a symptom—it feels like relief. And clinicians working from brief symptom checklists may not ask the right questions to uncover it (Nestsiarovich et al., 2021; McIntyre et al., 2023).

Comorbidities create noise. Anxiety, substance use, self-harm, and personality pathology frequently co-occur with bipolar disorder and can obscure the underlying mood cycling. These conditions are themselves risk factors for later "conversion" from an MDD diagnosis to a bipolar diagnosis (Nestsiarovich et al., 2021).

System factors compound the problem. Short appointments, fragmented care across multiple providers, reliance on checklist-based assessment, and lack of collateral history all contribute to diagnostic error. Patients may receive different diagnoses from different providers—leading to worse outcomes and higher healthcare costs (Bessonova et al., 2020).

The Treatment Stakes Are High

Getting this distinction right matters enormously for treatment. Antidepressants prescribed without mood stabilizers can destabilize bipolar disorder, potentially triggering rapid cycling, mixed episodes, or treatment resistance (McIntyre et al., 2023). Many patients labeled as having "treatment-resistant depression" actually have unrecognized bipolar disorder—their antidepressants aren't failing, they're targeting the wrong condition.

Conversely, being incorrectly diagnosed with bipolar disorder when you actually have BPD, ADHD, or trauma means receiving medications you don't need while missing treatments that could actually help. Mood stabilizers won't address the emotional dysregulation of BPD, which responds to specific psychotherapy approaches like DBT. Stimulants for ADHD work differently than mood stabilizers for bipolar disorder. Trauma-focused therapy addresses root causes that medication alone cannot touch.

The diagnosis determines the treatment map. A wrong diagnosis means following the wrong map—and wondering why you never arrive at feeling better.

INFOGRAPHIC: "MDQ Screening vs. Comprehensive Evaluation" — Visual comparing what MDQ captures (symptom checklist, single timepoint, self-report only)

The Bottom Line

The MDQ is a screening tool, not a diagnostic test. A positive score indicates the need for comprehensive evaluation—nothing more. With a positive predictive value around 34%, only about one-third of people who screen positive actually have bipolar disorder (Zimmerman et al., 2009). The tool cannot reliably distinguish bipolar disorder from borderline personality disorder (Zimmerman et al., 2010), and it misses the nuanced differential diagnosis required for accurate treatment planning.

If you've screened positive on the MDQ, or if you've been treated for depression without adequate response, the next step isn't another online quiz. It's a comprehensive psychological evaluation that includes structured diagnostic interviewing, thorough developmental and family history, assessment of comorbid conditions, and careful differential diagnosis.

Screened Positive? Don't Assume—Get Diagnosed.

A positive MDQ score tells you something is going on with your mood. It doesn't tell you what. Bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, trauma, ADHD—these conditions require different treatments, and the only way to know which map to follow is a comprehensive diagnostic evaluation.

Dr. Long provides expert diagnostic clarity completely virtually across 42 PSYPACT states, eliminating travel logistics and long wait times. Our digital process allows for seamless collateral input from family and providers, ensuring a thorough evaluation from the comfort of home.

For the fastest response (within 24 hours), please submit your request via our secure intake form:

Click Here to Complete the Nationwide Evaluation Request Form

Alternatively, if you prefer to email us, you may do so at david+referral@drlisalong.com. Please note that due to volume, email response times are significantly longer than form submissions.

Related Reading

The Misdiagnosis Crisis: Why Primary Care Misses Over 90% of Mental Health Conditions — Why screening tools alone aren't enough, and what falls through the cracks.

Social Anxiety vs. Generalized Anxiety in Young Adults: Why the Distinction Matters — Another example of how similar-looking conditions require different treatment approaches.

About the Author

Dr. Lisa Long, Psy.D., is a licensed forensic and clinical psychologist providing comprehensive psychological evaluations nationwide via PSYPACT-authorized telehealth. She specializes in diagnostic clarification for anxiety and mood disorders, particularly when prior treatment has been ineffective. Learn more about clinical evaluations →

Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes and does not constitute a professional psychological opinion or diagnosis. If you're struggling with mood symptoms, treatment-resistant depression, or questions about whether you might have bipolar disorder, a comprehensive evaluation can provide personalized diagnostic clarity and treatment recommendations.

Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) © 2000 by The University of Texas Medical Branch. Reprinted with permission. Developed by Robert M.A. Hirschfeld, M.D. and colleagues.

References

Bauer, M. (2022). Bipolar Disorder. Annals of Internal Medicine, 175, ITC97–ITC112. https://doi.org/10.7326/aitc202207190

Bessonova, L., Ogden, K., Doane, M., O'Sullivan, A., & Tohen, M. (2020). The Economic Burden of Bipolar Disorder in the United States: A Systematic Literature Review. ClinicoEconomics and Outcomes Research: CEOR, 12, 481–497. https://doi.org/10.2147/ceor.s259338

Cantone, E., Urban, A., Cossu, G., Atzeni, M., Fragoso Castilla, P. J., Giraldo Jaramillo, S., Carta, M. G., & Tusconi, M. (2025). The Inaccuracy of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire for Bipolar Disorder in a Community Sample: From the "DYMERS" Construct Toward a New Instrument for Detecting Vulnerable Conditions. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(9), 3017. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14093017

Duffy, A., Carlson, G., Dubicka, B., & Hillegers, M. (2020). Pre-pubertal bipolar disorder: origins and current status of the controversy. International Journal of Bipolar Disorders, 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40345-020-00185-2

Hirschfeld, R. M., Williams, J. B., Spitzer, R. L., Calabrese, J. R., Flynn, L., Keck, P. E., ... & Zajecka, J. (2000). Development and validation of a screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder: the Mood Disorder Questionnaire. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(11), 1873–1875. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.157.11.1873

McIntyre, R., Alsuwaidan, M., Baune, B., Berk, M., Demyttenaere, K., Goldberg, J., ... & Maj, M. (2023). Treatment-resistant depression: definition, prevalence, detection, management, and investigational interventions. World Psychiatry, 22. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.21120

Nestsiarovich, A., Reps, J., Matheny, M., Duvall, S., Lynch, K., Beaton, M., ... & Lambert, C. (2021). Predictors of diagnostic transition from major depressive disorder to bipolar disorder: a retrospective observational network study. Translational Psychiatry, 11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01760-6

Walter, M., Abright, M., Bukstein, M., Diamond, M., Keable, M., Ripperger-Suhler, M., & Rockhill, M. (2022). Clinical Practice Guideline for the Assessment and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Major and Persistent Depressive Disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2022.10.001

Yang, R., Zhao, Y., Tan, Z., Lai, J., Chen, J., Zhang, X., ... & Liu, X. (2023). Differentiation between bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder in adolescents: from clinical to biological biomarkers. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 17. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2023.1192544

Zimmerman, M., Galione, J. N., Ruggero, C. J., Chelminski, I., McGlinchey, J. B., Dalrymple, K., & Young, D. (2009). Performance of the mood disorders questionnaire in a psychiatric outpatient setting. Bipolar Disorders, 11(7), 759–765. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00755.x

Zimmerman, M., Galione, J. N., Ruggero, C. J., Chelminski, I., Young, D., Dalrymple, K., & McGlinchey, J. B. (2010). Screening for bipolar disorder and finding borderline personality disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 71(9), 1212–1217. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.09m05161yel